To learn value and appreciation for a thing, one must develop a relationship with said thing. Otherwise, it only remains a thing—to take or leave—without care, without consideration if the thing is here today or is here 100 years from now, or 500 years from now. This is a moral and ethical dilemma that we have trouble getting right and sticking it as a species.”

—Mina Thevenin, LCSW

BALD EAGLE: King of Birds!

Article by Mina Thevenin

Published April 20, 2019

Contributing Photographers

Cover Photo Credit Julie Holloway

Mating & Mated Bald Eagle Pairs: Julie Holloway, Tony Egbert, Lynn Bartlett, and Mina Thevenin

Contributing Photographers Continued

Nesting Bald Eagles with Eaglets: Lynn Bartlett, Mina Thevenin. Photography World™ gives special thank you to Decorah Eagles for their 2019 nesting images.

Juvenile Bald Eagles: Phillip Brown, Lynn Bartlett, Mathew Schwartz, Cosmic Timetraveler, and Mina Thevenin

Adult Eagles: Richard Lee, Bryan Hanson, Sandy Scott, Thomas Benson, Ray Hennessy, Alex Makarov, Don Mingo, Kea Mowat, Nelin Reisman, Heather Mount, Tony Egbert, Lynn Bartlett, Jongsun Lee, and Mina Thevenin

How do we learn to value the Bald Eagle?

How and why would we want to have a relationship with this thing?

Why care? After all, it’s just a big bird, very awesome though, but it’s still just a big bird to many.

Building & Keeping Relationships is a process.

HISTORY OF THE BALD EAGLE. Value develops when we learn about this magnificent raptor’s history and how it came to be chosen as the emblem of America’s Great National Seal.

THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHY, we learn about the Bale Eagle’s mating for life, its nesting and life as an adult.

PROTECTING THE BALD EAGLE FROM OURSELVES, a survivor of DDT poisoning and now faced with lead poisoning, the Bald Eagle brings people together to become proactive.

BLACK MARKET TRADING. We learn to value the Bald Eagle by enforcing laws and prosecuting those who break them.

To understand its history and these chapters of determination and survival—its story—this helps us to value the apex of raptors, the king bird, and its legacy as BALD EAGLE: KING OF BIRDS! A true champion in the ring of life

Choosing America's Great National Seal

Benjamin Franklin had it all wrong!

His forgone conclusions that the Bald Eagle was lazy, cowardly, and not original to the country was incorrectly cited in a letter to his daughter. This letter, which was never even intended to be sent to her, was intentionally written to serve as a political opinion piece about political events of the times.

An excerpt in the “letter” to his daughter, Sarah Bache, Dr. Franklin writes,

26 January 1784

“For my own part I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country. He is a bird of bad moral character. He does not get his living honestly. You may have seen him perched on some dead tree, where, too lazy to fish for himself, he watches the labour of the fishing hawk; and when that diligent bird has at length taken a fish, and is bearing it to his nest for the support of his mate and young ones, the bald eagle pursues him, and takes it from him. With all this injustice, he is never in good case, but like those among men who live by sharping and robbing he is generally poor and often very lousy. Besides he is a rank coward: the little king bird not bigger than a sparrow attacks him boldly and drives him out of the district. He is therefore by no means a proper emblem for the brave and honest Cincinnati of America, who have driven all the king birds from our country, though exactly fit for that order of knights which the French call Chevaliers d’Industrie. I am on this account not displeased that the figure is not known as a bald eagle, but looks more like a turkey. For in truth, the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird, and withal a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey was peculiar to ours, the first of the species seen in Europe being brought to France by the Jesuits from Canada, and served up at the wedding table of Charles the ninth. He is besides, (though a little vain and silly tis true, but not the worse emblem for that) a bird of courage, and would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British guards who should presume to invade his farm yard with a red coat on.” (1)

Imagine the turkey (picture top right) with olive branch and arrows clutched in either 3-toed foot, red white & blue shield on its breast. Its characteristic snood hanging down to the side of its beak and the originally adopted national motto—E Pluribus Unum— on waving ribbon, flowing around its dangling wattle and beard. The Bald Eagle was not almost the national symbol and great seal. It was historically never in the running, but it is fun to poke at Dr. Franklin’s interesting comparison of the two birds.

SEAL OF THE UNITED STATES

The “Seal of the United States”, as it was officially referred to in those words as approved by the act of Congress in August on September 15, 1789, finally declared on June 20, 1782 the final emblem: an amalgam (comprised by the 3 earlier committees) as created by the Secretary of Congress—CHARLES THOMSON, then aged 52.

Thomson combined the following:

1st committees approval in 1776:

- The Eye of Providence in a Radiant Triangle and the date MDCCLXXVI

- The Shield and latin motto, “E pluribus Unum” as submitted by artist Du Simitière and as adopted from its regular use in the London magazine publication Gentleman’s Magazine (1731-1922) The latin phrase, which most likely ultimately originated from Virgil or Horace, came to be adopted as the United States motto: “Out of Many, One”: E pluribus Unum.

The 2nd committee’s approval as primarily determined by Francis Hopkinson in 1780:

- Symbols of war (sword) and peace (olive branch)

- Crest with radiant constellation of 13 stars and a Shield with 13 stripes, alternating red and silvery-white

3rd committee retained the help of the self-ascribed authority on emblems and heraldry, Philadelphia lawyer William Barton in May, 1782:

- Retained the previous committees approvals

- Added the Bald Eagle as “displayed”.

Interestingly, Charles Thomson conferred with William Barton about Thomson’s own amalgam of all 3 committees approvals of the emblem, but Thomson’s eagle depicted the wings as rising. Barton suggested that he change the wing position to displayed, which Thomson did, and Congress approved this final rendition of Thomson and Barton on June 20, 1782.

Though the emblem of the Great Seal cannot be attributed to just one or two people. It must be recognized that 3 committees of 9 men, including each committees advisors, and are the contributing authors to the final emblem. (2)

EMBLEMS FOUND IN ANTIQUITY:

A Significant Influence in Choosing the Eagle

In antiquities, the eagle was widely used in ancient Greece, Rome and Egypt, with eagle animal representing Jupiter in mythology. Emblems and crests with eagles as depicted in early 16th century illustration books were very popular in Europe. They depicted animals, latin phrases and heraldry. Coins were also produced in Europe with eagles, olive branches and thunderbolts.

Harvard library, as resourced from its online digital Hathitrust collection availble to the public, I reference the publication: The Mirrour of Maiestie or The Badges of Honor. 1618. In it are depicted two emblems we might hypothetically suggest that original Seal of the United States forefathers might have been influenced by. Emblem #3 depicts a phoenix rising from flames with wings displayed and an olive branch in its mouth. Emblem #4 depicts phoenix holding a crown with olive branches in left talons (the phoenix head is in profile and looks left), with sword held in right talons. Described in the text below the emblem, in old English, “This Embleme of foft peace and warlike bands”. (3)

Is is factually known that Benjamin Franklin owned a copy of the 1702 copy of the publication: Joachim Camerarius’ Four Centuries of Ethico-Political Symbols and Emblems. This was a collection based on the animal kingdom—which included birds—of 400 emblems, mottos, explanations and essays written in Latin. According to the Library Company of Philadelphia, which houses Benjamin Franklin’s library, they note:

| Benjamin Franklin’s copy. Contemporary full sprinkled calf, rebacked; title bound in vol. 4. Franklin’s pencil numbers inside front covers of vols. 2–4: C22 N24-26; acquired by William Mackenzie; Mackenzie bequest in 1828 to Loganian Library. (4) |

According to Patterson’s 1978 publication through the United States Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, Dept. of State book, The eagle and the shield : a history of the great seal of the United States, Benjamin Franklin directly copied plates from the Camerarius books for emblem and motto designs for many of the newly printed Continental currency denominations.

Ultimately, then, it is not surprising to consider that the forefathers in those committees were directly influenced by and borrowed images, mottoes and themes from previously published and well-known related writings that were popular in the day and in the preceding centuries.

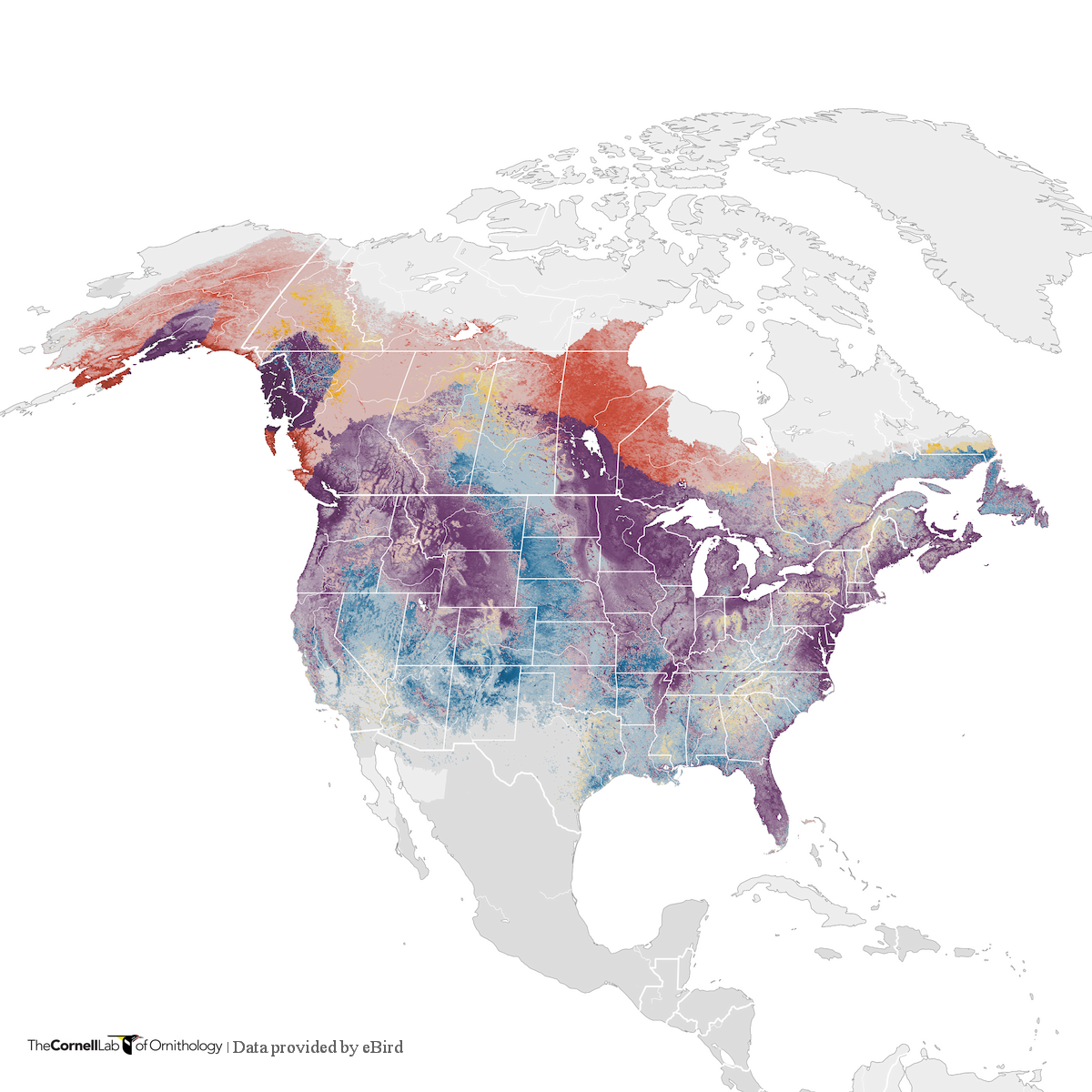

21st Century Migration, Year-Round, & Breeding Areas

Eagles Mate for Life

WHITE HEADS & TAILS OF EAGLES

Maturing when they are 4 to 5 years old, their head feathers turn white, a clear indicator that the juvenile eagle is now an adult—sexually mature—and ready to mate.

Eagles are monogamous and mate for life unless there is death of a mate, one doesn’t return to the nest, or mated pair are unable to produce offspring. During non-mating season, they do not pair together.

Monogamy and mating for life have two separate meanings. “MONOGAMY”, in ornithology, means a male and female bird pairing together or that they become a pair bond. According to scientists, about 90 percent of bird species are socially monogamous, and that true monogamy among birds is the exception rather than the rule. Monogamy for mating may last through one nesting season, several seasons, or for life. “MATING FOR LIFE” is the annual mating between the same bonded pair for a life-time.

In the bird world, there are a limited number of mate-for-lifers. BALD EAGLES are counted as one of the seven raptors. (For a complete list see below.)

EAGLE COURTSHIP It looks like fighting, but it is not. (See photographer Tony C. Egbert’s courtship photo below.) It is eagle bonding. It is a demonstration of their strength and agility. Dramatic displays involve swooping and stick exchanges. The most dramatic courting behavior is their death-defying, talon clutched aerial spiral. In midair they eagles’ talons clutch together. One eagle flies upside down and they rapidly loose altitude. The pair release talons before plunging to death, giving a whole new meaning to human’s idea of “proving your love” baby.

HOW and WHERE DO EAGLES MATE? Eagles do not mate while flying. They mate on a branch near the nest or in the nest that they will use (eagles will reuse the same nest each year when viable). The male mounts the female and copulation occurs. Sperm is transferred during copulation, when the cloaca of the male and female touch; this is known as the cloacal kiss. Copulation may occur several times a day over a period of days. (7)

Bald Eagle pair, audio recording within one minute after mating, (image right). Kentucky, January 2019, recorded by author Mina Thevenin

Galleries

Recycled Nests

An example of a 2019 nest with partial collapse after a straight line wind storm. One surviving eaglet is seen in nest (top).

BALD EAGLES have a strong nest site fidelity.

They return to the same nesting territory and often the SAME NEST each year, especially if they had a successful brood of eaglets the previous year. HOUSEKEEPING. They repair weak areas with new branches and reline the soft interior bowl with grasses, moss (may serve as an insect repellent), silky corn stalks, and downy feathers from the adult. These nests are very sturdy and can weigh 1/2 a ton to an excess of one ton.

Average size bald eagle nests are 4 to 5 feet in diameter and 2 to 4 feet deep. Each year the adult pair will add 1-2 feet of new material to the nest.

Bald Eagles choose trees near large bodies of water such as lakes, reservoirs, rivers, marshes, and coasts. This raptor is truly a sea eagle. Preferred nesting sights are tall trees with open areas at the top, and forked limbs (ideally three limbs or more) like a cradle for constructing the nest securely. In geographic areas that lack trees for nesting, i.e. Alaska, the Bald Eagle may nest on the ground.

How long does it take to build a nest?

Considered part of the breeding process, nest construction begins 1-3 months prior to mating season. If it is a new nest, it will generally take 1-3 months to build, with both male and female participating in the nest building. When eagles reuse and recycle their nest from last year, they may increase the size by up to a foot in height and diameter., with repairs and improvements. Nest building and fixing continues even after the eggs have hatched. Many bald eagles in the Upper Mississippi River valley engage in some nest building in as early as November when the photo period is similar to that of their spring breeding season when they are actively nest building.

Bald Eagles will abandon a nest for numerous reasons: nest collapse due to weather, human contamination in the area, tree falls down, or the mated pair did not successfully produce a living brood of eaglets from the previous year. Bald Eagles do sometimes have a second nest in the area, of which they have also been constructing, and may decide to nest in the second location. (8)

Galleries

What Do Bald Eagles Eat?

BALD EAGLE DIET consists primarily of fresh catch—FISH—when they can get it!

Both parents will feed eaglets by tearing catch and feeding it to their young. Bigger and healthier eaglets get more food. Benjamin Franklin was correct, that Bald Eagles do scavenge meals by harassing other birds and taking their catch. What else is on the menu beside fish? Mammals, waterfowl, snakes, frogs, turtles, are also on the menu. Although they mainly eat fish, they will also eat carrion or pick through garbage when necessary. (Similar to other animals, including humans.)

From EGGS to EAGLETS to FLEDGLINGS to JUVENILES

Climate and geographic latitude effects the timing of breeding and egg laying. For this North American raptor, southern states means earlier egg-laying, i.e. November in Florida, whereas Alaska in the north may occur late April through May.

EGG LAYING After a successful copulation, the female lays from 1-3 eggs in approximately 5-10 days. The average clutch, or group of eggs, is 1-3; the eggs are off-white and approximately 3 inches long by 2 inches wide. Each egg weights about 4-4.5 oz. Eggs are laid one at a time with 1-2 days in between each egg laying. They hatch in the order in which they were laid. In southern states it is possible for there to be a second brood if the first clutch did not survive incubation.

EGG TURNING Both parents take turns rolling the eggs every couple of hours to prevent yolk from settling.

BOTH EAGLE PARENTS incubate the eggs and take care of the nest. Eagle eggs incubate for a little over a month, approximately 35 days.

It can take a day for the hatchling to completely break free of the egg after pipping (cracking the egg).

Who incubates the egg?

Because the laid egg must be kept warm and protected from predators, both parents alternate sitting on the egg(s). It is the female, however, who usually spends more time on the nest at night and in inclement weather, because she is bigger and can cover the eggs more effectively. At night only one eagle incubates the eggs. The other parent eagle roosts elsewhere. Males leave the nest to hunt, often providing food for the female. However, the female will sometimes leave the nest to hunt for herself, at which times the male will be called upon to remain at the nest. Especially when the eaglet gets older, the female will do more hunting. Additionally, as the eaglet (who firstly develops white fluffy feathers, that turn to a gray as it ages) gets older, both parents will leave the nest for 20-30 mins.

FLEDGING Bald eagles fledge at about 2-3 months, or 10-14 weeks. Before their first flight, nestlings will flap their wings in the nest or jump to an adjacent branch in behavior known as branching. Fledglings are usually full-grown adult eagle size by the time they fly the nest. Their coloring becomes a mottled brown with no white. There may be some minimal growth after that.

JUVENILES, or immature birds, have mottled feather colors with no white head nor white tail. At the age of 4 and 5, the juvenile begins to get whiter feathers on head and tail. After age 5, the now adult eagle has its life-long plumage of white head and white tail; it is not possible to visually tell the age of an eagle after age 5. This is also the age when a Bald Eagle reaches sexual maturity and is ready to mate.

Studies indicate that juveniles are generally nomadic in the first four years of their life and can cover extensive geographic areas. Studies also show that when the juveniles are ready to mate, they tend to return to the general area where they were born. They do not return to the nest where they were born (9), but they may do a fly-by to say hello! (Read more in author’s upcoming book about Bald Eagles.)

Image above, by Lynn Bartlett, an eaglet and parent Bald Eagle in nest. Image directly below, by Mathew Schwartz, head and tail have less white than adult eagle in top image.

Galleries

Adult Bald Eagles

HOW HIGH CAN YOU SOAR?

Soaring above 10,000 feet, the Bald Eagle can fly at a height of over 1 1/2 miles.

SIZE. Smaller than the female, the adult MALE Bald Eagle is about 36 inches long and has a wingspan of 6.6 feet. Females may reach 43 inches in length and have a wingspan of 8 feet.Eagles can weight up to 15 pounds, but average weight is 10-14 pounds. Contrary to urban and rural myth, an eagle can only carry up to 1/3 of its body weight. ADULT COLORING. Both sexes are dark brown, with a white head and tail. It’s beak, eyes, and feet are yellow. Bald Eagles in the wild can live to be EAGLE EYES. Their vision is 4 times more acute and perfect than a human’s vision, even though their eye is about as large as our eyeball.

Because they do not sweat, Bald Eagles pant. This is how they cool their body temperature (which normally runs at about 106 degrees Fahrenheit). They also perch in shade and hold wings slightly away from their body.

VOCALIZATION. Not much research has been done about Bald Eagle vocalizations. General studies and assumptions have lead current researchers to attribute basic calls to rudimentary cognitive functions between birds and within nesting families. This author disagrees with these basic assumptions and ventures to hypothesize that, like many creatures in the animal kingdom, the Bald Eagle has a vast repertoire of sound-vocabulary that we just have not studied. (i.e. please refer to author’s Photography World article about Prairie Dogs, particularly the vocalization research by Con Slobodchikoff, PhD .) Additionally, my own observations of nesting Bald Eagles identifies covert and overt behavioral and vocal communications between them.

LIFE EXPECTANCY Eagles in the wild can live to be approximately 20-25 years old, although those in captivity can live to be into their 30-40’s. Getting to adulthood is challenging, with only 20-30% of juveniles making it to age 5. (10)

Galleries

THE PROBLEMS WITH USING PRODUCTS THAT ARE POISONS.

Because this sea eagle RAPTOR is the apex of birds, it is most susceptible to toxins found in the environment, as each link in the food chain tends to concentrate chemicals from the lower link. Bald Eagles eat the lower links and thus the build-up of toxic chemicals in their systems. This is very similar to human poisoning as we ingest our food chain and thus are exposed to very similar toxins just as the Bald Eagle is.

EXPOSURE TO TOXINS Historically was the well known pandemic of DDT pesticide poisoning from post WWII to 1962. How was DDT causing damage? Pesticide use for bug control resulting in field run-off contaminated waters where Eagles (and people) fished, the fish became poisoned, the birds ate the fish and calcium levels were decreased—thus egg shells were to thin to survive incubation.

Many people and organizations are credited with banning the use of DDT. CHARLES BROLEY (a retired bank manager from Winnipeg Manitoba, Canada) began banding Florida Bald Eagles in 1939 for the National Audubon Society, to study the migration of nesting adults. In the early 1940’s he was banding 150 eagles a season. By 1947 he reported fewer eaglets and identified that 41% of nests failed to produce any young. By 1950 the failure rate had increased to 78%.

National Audubon Society organized formal surveys during those 4 decades and continued to spearhead studies; they worked closely with the Fish and Wildlife Service. In 1960 the conservation group launched its national survey, the Continental Bald Eagle Project. They gathered data from eagle watchers, the F & W Service, state and national game management agencies; they counted and tracked Bald Eagle population, migration and nest success/failure by also scientifically studying failed eggs. Some statistics for example, showed that in 1962 when they joined with a Chesapeake Bay study already in progress—utilizing aerial surveys as supported by military personnel, as well as, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service—that “covered approximately 80% of the available shoreline and located a total of 54 active nests (34 in Virginia). Alarmingly, of the 28 nests rechecked, only 3 produced young.”(11)

Four decades of research concluded it was DDT. This culmination of mounting horrific evidence the the Bald Eagle populations across the United States and Canada,(except Alaska and the Pacific Northwest) were teetering on extinction, sparked the interests for author and marine scientist RACHEL CARSON . In 1962 she published her landmark and politically influential book, Silent Spring. This forever changed citizens and politics, creating near immediate and significant changes after Congressional hearings involving Rachel Carson’s testimony, decided to ban many of the pesticides cited in her book. Congress amended FIFRA to consider safety relabeling of pesticides. Among the pesticides the EPA banned was DDT in 1972. “The Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 was Silent Spring’s greatest legal vindication. It directed the EPA to protect the public from “unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment.” Under its authority, the EPA acted to ban or severely restrict all six compounds indicted in Silent Spring—DDT, chlordane, heptachlor, dieldrin, aldrin, and endrin—and assumed responsibility for testing new chemicals.”(12)

FROM ENDANGERED TO SUCCESSFUL DELISTMENT

In 1967 the Bald Eagle was listed as endangered—a species faces possible extinction—in the lower south 40 of the United States, and in 1978 the listing was expanded to include the lower south 48 states. “Listing the species as endangered provided the springboard for the Service and its partners to accelerate the pace of recovery through captive breeding programs, reintroduction efforts, law enforcement, and nest site protection during the breeding season.”(13)

WHERE ARE WE AS OF 2019?

Current dangers to Bald Eagles include lead poisoning, wind turbines, electrocution, habitat destruction, and predator upon the egg, eaglet, or juvenile.(14)

There is also the illegal activity of poaching. Continue reading below: Sold to the Highest Bidder! Black Market Trading 21st Century Style.

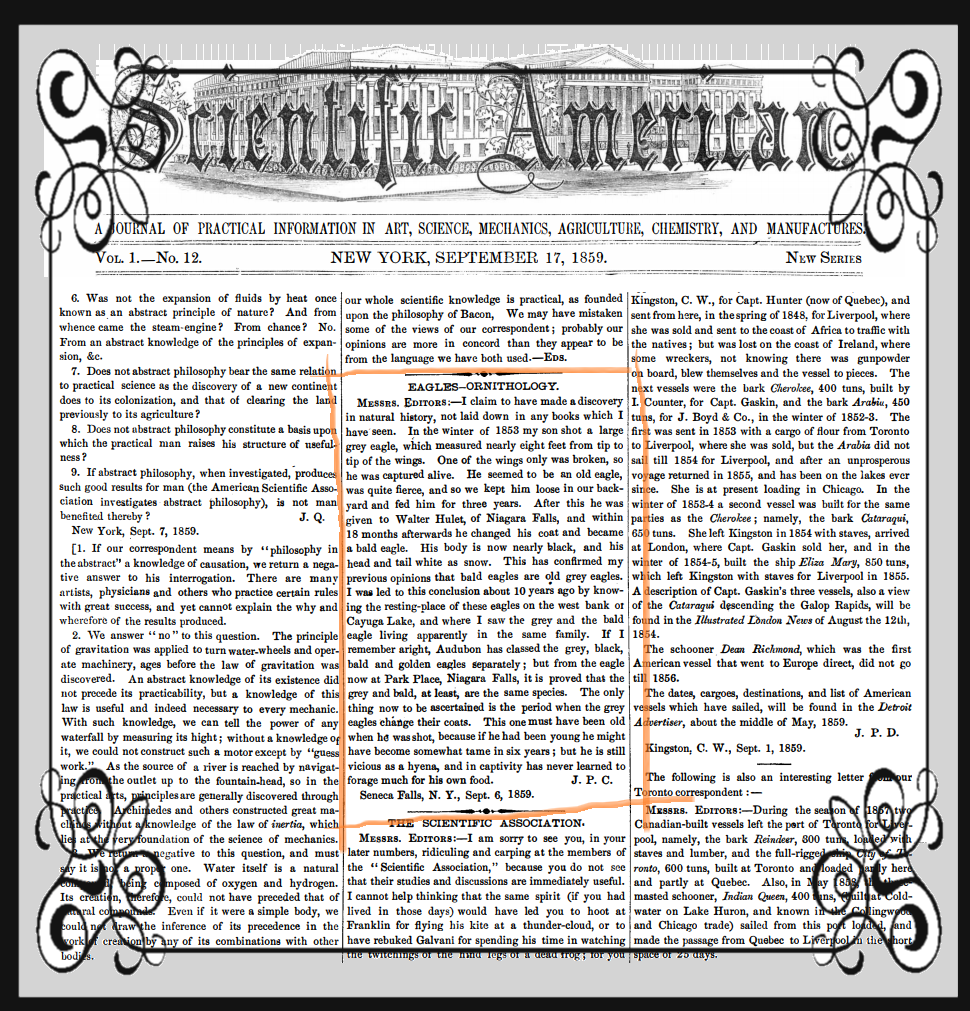

Sold to the Highest Bidder!!! Black Market Trading 21st Century Style

Colorful bird plumage has been sold, traded and coveted for centuries. It has been a contributing factor to near extinction for many birds. To use feathers in fashion, i.e. historically hats, promotes animal suffering and killing: birds for feathers.

Eagles are federally protected by 2 laws, so what is happening today with Bald Eagles? Isn’t the protection act enough?

Bald & Golden Eagle Protection Act

The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (16 U.S.C. 668-668c), enacted in 1940, and amended several times since, prohibits anyone, without a permit issued by the Secretary of the Interior, from “taking” bald or golden eagles, including their parts*, nests, or eggs. The Act provides criminal penalties for persons who “take, possess, sell, purchase, barter, offer to sell, purchase or barter, transport, export or import, at any time or any manner, any bald eagle … [or any golden eagle], alive or dead, or any part*, nest, or egg thereof.” The Act defines “take” as “pursue, shoot, shoot at, poison, wound, kill, capture, trap, collect, molest or disturb.” “Disturb” means: “to agitate or bother a bald or golden eagle to a degree that causes, or is likely to cause, based on the best scientific information available, 1) injury to an eagle, 2) a decrease in its productivity, by substantially interfering with normal breeding, feeding, or sheltering behavior, or 3) nest abandonment, by substantially interfering with normal breeding, feeding, or sheltering behavior.”

In addition to immediate impacts, this definition also covers impacts that result from human-induced alterations initiated around a previously used nest site during a time when eagles are not present, if, upon the eagle’s return, such alterations agitate or bother an eagle to a degree that interferes with or interrupts normal breeding, feeding, or sheltering habits, and causes injury, death or nest abandonment. A violation of the Act can result in a fine of $100,000 ($200,000 for organizations), imprisonment for one year, or both, for a first offense. Penalties increase substantially for additional offenses, and a second violation of this Act is a felony.(15)

I need Bald Eagle feathers for my religion.

The same Bald Eagle Protection Act also includes that the Service of Fish & Wildlife Protection offers Native Americans access to the National Eagle Repository—a clearinghouse for eagle feathers and (dead) eagle parts—for religious use by Native Americans.

The Repository collects dead eagles salvaged by

The Repository collects dead eagles salvaged by

Federal and State agencies, zoos, and other organizations. Enrolled members of federally recognized tribes (as established under the Federally Recognized Tribal List Act of 1994, 25 U.S.C. Section 479a, 108 Stat. 4791)

may obtain a permit from the Service authorizing them to receive and possess eagle feathers and parts from the Repository. Permit applications must include certification of tribal enrollment from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Because demand is high, waiting periods exist.”(16)

What is the old adage: one bad apple can spoil the barrel?…how many bad apples can there be?…

A May 16, 2017 article

“Fourteen appear in court for eagle trafficking

by Danielle Ferguson from the South Dakota’s Argus Leader, writes

“Fourteen people appeared in court this month for their involvement in illegally trafficking eagles and other migratory birds. Authorities are still looking for another man facing the same charges.

The appearances come after a two-year undercover operation by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service called Project Dakota Flyer.

Officials expect significant federal charges, said U.S. Attorney Randy Seiler. The case focused on trafficking eagles and eagle parts and feathers for profit. The case so far involves more than 100 eagles, but could climb up to 250.

One of the operations was described as a “chop-shop for eagles,” Seiler previously said. Eagle feathers were stuffed into garbage bags and talons and beaks were made into merchandise.”

Image left: Photo Faulk County Sheriff’s Office: This eagle was found shot in rural Falk County South Dakota, northwest of Faulkton. The sheriff’s office is offering financial reward to those who can provide information to who shot the bird.

On Thursday, August 2, 2018, the United States Attorney’s Office of South Dakota released a press announcement of their 1 1/2 year sting operation: PROJECT DAKOTA FLYER. Exposing and prosecuting this particular underground black market sales of nationally protected Bald Eagle feathers and body parts can hopefully effect other would-be criminals from engaging in such unlawful activity.

The Department of Justice press release is as follows:

OF THE BIRDS THAT MATE FOR LIFE, MOST ARE PROTECTED BIRDS

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 makes it illegal to take, possess, import, export, transport, sell, purchase, barter, or offer for sale, purchase, or barter, any migratory bird, or the parts*, nests, or eggs of such a bird except under the terms of a valid Federal permit. Migratory bird species protected by the Act are listed in 50 CFR 10.13. (17)

P.L. 105-312, Migratory Bird Treaty Reform Act of 1998, amended the law to make it unlawful to take migratory game birds by the aid of bait if the person knows or reasonably should know that the area is baited. This provision eliminates the “strict liability” standard that was used to enforce Federal baiting regulations and replaces it with a “know or should have known” standard. These amendments also make it unlawful to place or direct the placement of bait on or adjacent to an area for the purpose of taking or attempting to take migratory game birds, and makes these violations punishable under title 18 United States Code, (with fines up to $100,000 for individuals and $200,000 for organizations), imprisonment for not more than 1 year, or both. The new amendments require the Secretary of Interior to submit to the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works and the House Committee on Resources a report analyzing the effect of these amendments and the practice of baiting on migratory bird conservation and law enforcement. The report to Congress is due no later than five years after enactment of the new law.

P.L. 105-312 also amends the law to allow the fine for misdemeanor convictions under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act to be up to $15,000 rather than $5000.(20)

RAPTORS

EAGLES

- Bald Eagles (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

- Golden Eagles (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

- Philippine Eagles

BARN OWL(protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

BLACK VULTURES

CALIFORNIA CONDORS (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

GYRFALCONS (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

OSPREYS (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

RED-TAILED HAWKS (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

AUK Family, ALCIDAE

- Atlantic Puffins aka Common Puffin (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act (Vulnerable)

COLUMBIDAE

- Mourning Dove aka rain dove (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act

- Pigeon aka Rock Dove, or Feral Pigeon

CORVIDAE

- Blue Jay (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

- Pinyon Jays (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

- Black-Billed Magpies aka American Magpie

- Crows (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

- Ravens (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

- Rooks (Eurasia)

- Jackdaws (Eurasia, North Africa)

CRANES

- Brolgas (Australia, New Zealand)

- Sandhill Cranes (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

- Whooping Crane (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

DIOMEDEIDAE Seabird

- Laysan Albatross (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

GEESE

- Canada Geese (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

- Snow Geese (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

OLD WORLD WARBLERS (Sylviidaes)

- Wrentit (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

PARROTS

- Scarlet Macaws (South America)

PERIDAE

- Oak Titmouse (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

PICIDAE

- Pileated Woodpeckers (protected under the U.S. Migratory Bird Treaty Act)

SWANS

- Bewick’s Swans (United Kingdom)

- Black-Necked Swans (South America)

- Mute Swans (Eurasia, North Africa, Introduced to South Africa, Australia and North America

Footnote (18)

HUMAN BEINGS & THE BALD EAGLE

Do you value this thing? Do you care if it is here tomorrow or in a million tomorrows?

EDUCATION and CONVERSATION I attended a conservation and Bald Eagle rehabilitation program in January of 2019. The group was from St. Louis and provided an educational talk about raptors. Afterwards I talked with the presenter to understand her impressions about the impact that education, like this, is having on children of today.

She assured me, “I can see it in their eyes,” she said about the grade school age audiences. “We are reaching them about the importance of taking care of nature and wildlife.”

It truly is up to people— we affect change across our planet—to develop relationships with Bald Eagles and put into practice how we can both successfully live in this world. Not to just survive, but to thrive.

As a philanthropist, writer and photographer, I am continuing my studies about the Bald Eagle and will be publishing a book later this year.

To love a Bald Eagle is easy because it is majestic and powerful. To love the undesirable, that is the turning point for humanity.

Mina Thevenin, LCSW

REFERENCES

1.“Founders Online: From Benjamin Franklin to Sarah Bache, 26 January 1784.” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-41-02-0327#BNFN-01-41-02-0327-fn-0015.

2.United States, Congress, “The Great Seal of the United States.” The Great Seal of the United States, U.S. Dept. of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, 1996.

3. Editors Green, Henry, and Croston, James. ed. The Mirrovr of Maiestie or The Badges of Honor. Conceitedly Emblazoned. A Photo-Lith Facimile reprint from Mr. Corser’s Perfect Copy. A Brother’s Saint Ann’s Square, Manchester and Trubner & Co., Paternoster Row, London. England. 1618. Harvard Digital Library, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044025691361. Web. 21 March 2019.

4. Camerarius, Joachim,1534-1598. Joachimi Camerarii symbolorum ac emblematum ethico-politicorum : centuriae quatuor. … : non solum proprietates, sedetiam eruditorum sapientumq[ue] vivorum sententias & dicta memorabilia artificiosa & historica methodo describit : opus cuivis hominum statui, utile, jucundum & proficuum : 400. figuris aeneis adornatum. Moguntiae [Mainz] : Sumptibus Ludovici Bourgeat, 1702.

5. Migration Maps The Cornell Lab, Department of Ornithology

6. eBirds Abundance count map key

7. “Eagle Nesting & Young.” National Eagle Center, 9 Mar. 2019, www.nationaleaglecenter.org/eagle-nesting-young/.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. National Eagle Center, 10 Mar. 2019, https://www.nationaleaglecenter.org/learn/biology/

11. “Annual Survey.” The Center for Conservation Biology, https://ccbbirds.org/what-we-do/research/species-of-concern/virginia-eagles/annual-survey/

12. Rachel Carson. Silent Spring. 1962. Commentary @ http://www.environmentandsociety.org/exhibitions/silent-spring/us-federal-government-responds

13. Service, U. S. Fish and Wildlife. “Fact Sheet: Natural History, Ecology, and History of Recovery.” https://www.fws.gov/midwest/eagle/recovery/biologue.html

14. American Bald Eagle Foundation. “Dangers Facing Bald Eagles.” https://www.eagles.org/what-we-do/educate/learn-about-eagles/bald-eagles-current-dangers/#toggle-id-1

15 Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife. “Digest of Federal Resource Laws of Interest to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” Official Web Page of the U S Fish and Wildlife Service, https://www.fws.gov/birds/policies-and-regulations/laws-legislations/bald-and-golden-eagle-protection-act.php.

16 Possession of Eagle Feathers and Parts by Native Americans. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, www.fws.gov/eaglerepository/factsheets/PossessionOfEagleFeathersFactSheet.pdf.

17. Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife. “Digest of Federal Resource Laws of Interest to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.” Official Web Page of the U S Fish and Wildlife Service, www.fws.gov/laws/lawsdigest/MIGTREA.HTML.

18. Ibid.

I like what you guys are up too.

Hmm it seems like your website ate my first comment (it was

extremely long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I wrote and say,

I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog.

Hello there! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to say I truly enjoy reading your articles!

Catherine, thank you for leaving your first comment and grateful that it’s kind! Hope you keep coming back!