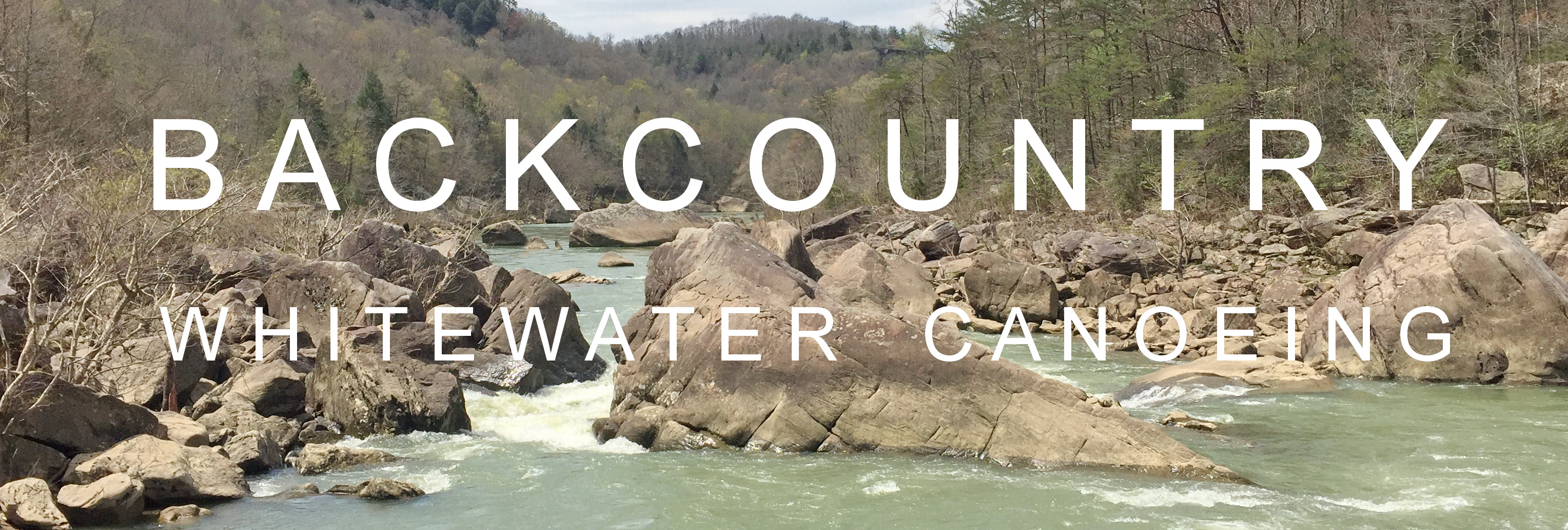

WHITEWATER CANOEING

BACKCOUNTRY On Cumberland River’s

Big South Fork,

A Class Action Spring Run!

By Mina Thevenin

Whitewater canoeing is a high risk sport that is potentially life threatening. Backcountry whitewater canoeing (BWC) involves not only time on the water, but also portaging gear and camping in the wilderness without access to cellphone coverage, medical treatment facilities, food stores or fresh drinking water. What you take with you on a trip is all that you have to survive and rescue yourself and your crew. This includes water, food, maps and charts, rescue equipment and extra clothes. Dangers include, but are not limited to: weather and heat/cold related illnesses like sunburn, sun poisoning, or the cold of hypothermia and frostbite, trenchfoot, physical accidents and/or health related emergencies (i.e. heart attack), and death. Physical and mental rigors associated with these activities are inherently dangerous and represent an extreme test of a person’s physical and mental limits and conditions. While this article is written for entertainment purposes only,

Photography World advises anyone interested in whitewater canoeing to do careful research before going and to only go with a registered and qualified whitewater company associated with the America Outdoors Association outfitters or similarly trained expert outfitter. The American Canoe Association and Professional Paddlesports Association (sponsored by the AOA) also provides a wealth of valuable information about canoeing and safety. Specifically, the Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife has a page specifically on the Big South Fork; it provides informative educational material for those interested in going to this region. Remember, your personal flotation device (PFD) is always worn in and/or around the water. Your life jacket can save your life: it did mine.

.

T H R E E T Y P E S O F A D V E N T U R E R S

.

1. E X P E R I E N C E D & E X P E R T S

.

2. B U C K E T L I S T

T H R I L L S E E K E R S

.

3. N O

” I could no longer hear the water when I was in it, for I had become one with the rapids and bowed to the mercy of its will, not mine.” —the Author upon capsizing.

For most people your bucket list does not include backcountry or whitewater open canoeing. In fact if you are asking yourself, “what is it?” then you are most likely at number three: no. Hopefully though, your list does include dayhiking and/or canoeing. For a small percentage of thrill seekers, you know who you are, your heart is beginning to race at the thought of such an adventure, but it is unlikely that whitewater canoeing is a “bucket list” activity. Most people who do whitewater paddling don’t do it impulsively. It is usually well thought out, planned and researched. Intermediate and experienced paddlers usually begin paddling at a younger age in their lives. You may own your own gear or rent from a whitewater livery. A small percentage of you, you are well-experienced and are approaching or are experts. Your pulse might not even increase much at all you are so experienced. Regardless of one’s adventure level, it is always smart to understand that things can go wrong very quickly. Safety and preparedness, whatever the type of adventure from leisurely daytrip to backcountry, is number one.

This article is not written from an expert’s perspective; it is, however, written with the intention to share what it is like to experience backcountry (also see the Photography World article, APPALACHIAN TRAIL: TAKE A WALK ON THE WILD SIDE) and whitewater canoeing as a naturalist and photographer.

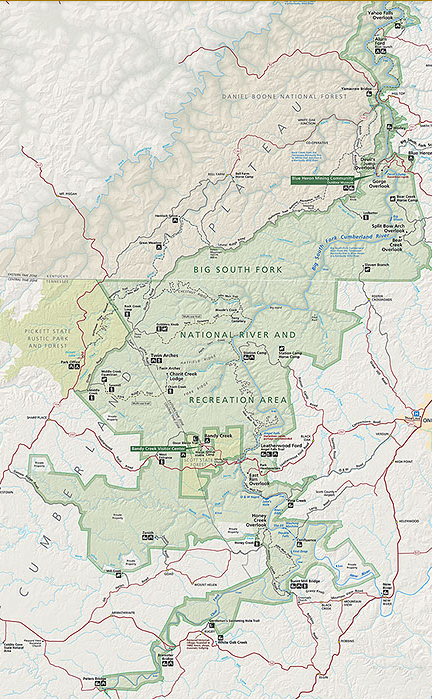

Map is a graphical representation designed for general reference purposes only. Courtesy of the National Park System

BACKCOUNTRY WHITEWATER CANOEING IN THE BIG SOUTH FORK

NATIONAL RIVER & RECREATION AREA

Backcountry in the Cumberland River’s line from Tennessee-Kentucky to the Blue Heron, KY, is pristine. It is a Tennessee-Kentucky 76 mile long wild river, a gorge that cuts through the Appalachian Mountains of the Cumberland Plateau. The Big South Fork is formed at the confluence of the New River and the Clear Fork of Oneida, TN, and extends north into Kentucky (1). The Big South Fork area is similar to Kentucky’s Red River Gorge, see the Photography World article, Red River Gorge: Just for the Hike of It, yet it is more remote and pristine. It gives rise to natural bluffs, a high concentration of natural bridges, and the interesting hoodoos- usually found mostly in North America’s western dry and desert regions. Though when you are on the river, especially running the river or parts of it during the higher water months of spring (possibly lower in fall and winter) in an open canoe, the many natural features that hiker’s can explore are missed from whitewater. Summer whitewater is a bit more leisurely and lends itself to sight-seeing, even if it’s mostly from the canoe.

Class rapids of the free-flowing (free-flowing means without any upstream reservoirs above the whitewater section) Big South Fork range from calm to challenging with greater water flow challenge opportunities in the spring, granting higher CFS (CFS is the flow of water measured in cubic feet per second. A cubic foot contains about 8 gallons of water) depending on rain fall. Runs will vary from Class I-IV, although depending on water levels and gear, smart decisions may need to be made to portage (carry all the gear including canoes) around a rapid given dangerous situations. In early spring because of water levels and higher CFS, extra portages are necessary. Paddlers must remain informed for up to date information about constantly changing weather conditions that affect not only the river, but backcountry camping as well. It is wise to follow local news, websites and updates for changes on the river. The U.S. National Weather Information System has up to date information @ http://waterdata.usgs.gov/nwis

R E S P E C T F O R N A T U R E

A PERSONAL TELLING

At any time of year backcountry camping with the correct survival gear, in addition to the list for whitewater canoe paddler, makes for an unforgettable adventure.

A personal account of spring and summer whitewater on the Big South Fork is paddling the difference between faster, opaque and deeper coffee-colored green whitewater (see Fig 1) and clear shallower whitewater (Fig. 2). Portages take place no matter what time of year it is. Weather always make a difference—just like dayhiking or canoeing in warm or cold weather— so be prepared.

SUMMER

Summer whitewater and backcountry camping invites swimming among the visible fish and a possible invitation to paddle Devil’s Jump (see Fig. 1) with its whitewater drop, dog-leg right.

Backcountry in summer is alive! The threat of hypothermia is a precautionary thought and plan in the back corner of the mind (hypothermia can occur even in water temperatures of 60 degrees Fahrenheit), so summer camping and whitewater open canoe is less stressful. As always, though, the sudden onset of threatening weather no matter what time of year it is, is a given. Summer brings pop-up storms with the potential for flash floods and lightening. Being self-prepared, having a good team and qualified outfitter is without question, mandatory.

Backcountry in summer brings a quiet for the soul. It is a reckoning of decision-making skills. The acceptance of being without. Whitewater canoeing and backcountry sets the personal clock to a rhythm that is river time. It is a time for the soul to reset and to listen, look, smell, feel: campfires, millions of stars, a Milky Way of water-drops that flow and spiral into one: the river. The flow of the river washes clean and renews the spirit. Camping along its sandy shores sets things right in an otherwise cross and sorrowful world—a reprieve from such—to an embrace of things eternal. This oneness washes over you, if you allow, and enchants the spirit back home to nature.

Does it last? Once you are aware of this rhythm of life flow, by which the river reminds us, it is with you always. It flows within and really has been always flowing. Backcountry and river reminds us of our roots.

SPRING

“BACKCOUNTRY WHITEWATER CANOEING IN SPRING IS A DIFFERENT BEAST ALL TOGETHER. IT’S LIKE GRABBING THE HUNGRY WINTER LION BY THE TAIL AND FIGURING OUT HOW TO HOLD ON WHILE IT CHARGES DOWN THE RAPIDS, ROARING AT FULL SPEED. SURE, IT LETS YOU SLEEP AT NIGHT IN FREEZING TEMPS, ONLY TO WAKE YOU UP TO CHASE IT ALL OVER AGAIN THE NEXT DAY.”

— the Author on BWC

Being off grid in the tail month of winter, even if it is called spring, besets all of the above with cold weather and wind. The inherent degree of challenge is heightened because of sleep deprivation. Even with proper gear for winter backcountry camping and wetsuits for whitewater open canoe, the cold is penetrating—worse at night. Personal fortitude? Having trekked a piece of the Oregon Trail and slept in 1800’s re-enactment tents during a summer squall, sleeping with several dozen mice in a North Carolina Appalachian Trail shelter…either are preferable to camping in -6.7 Celsius or 20’s Fahrenheit, with wind gusts up to 45 kph or 25 mph, in periods of cold rain. Having realized this truth, there is always a silver lining in any tale.

Spring backcountry: sounds travel farther than summer sounds. Fewer leaves, save for the thin needles of pine, do not buffer the calls of the wild. Night brings the thrilling calls of the Barred Owls with their common calls of “who cooks for you?” calls and monkey-sounds. Upon the final camp brings the sounds of the large Great Horned Owls, a duet of calls under a canopy of millions of stars…and wind.

Invisible song birds greet the morning sunrise. Excitement of the first day’s spring paddle and lack of sleep welcomes the important sense of survival. A seriousness in the air surrounds the day break campfire. Sharing a photo of the night-camp visitor to our dry bag, just twenty feet away from the tent, is met with unenthusiastic response. And seriousness.

Black bears have made a significant come back into the Cumberland Plateau region. Tom Blount with the National Park Service from the Big South Fork area identified the animal track in these images as black bear. He states that, “Black bears are now common throughout the park. Back county users should follow the food storage requirements for back country camping in order to keep bears wild.” https://www.nps.gov/biso/planyourvisit/foodstorage.htm

Since 1996 and ’97, 14 females were released from their capture in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. A cooperative project to understand and study relocation techniques, “as well as to help determine whether the area contained adequate habitat and food sources to support black bear,” was supported by a cooperative between the National Park Service, Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency, Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources, USFS-Daniel Boone National Forest, and USGS-Biological Resources Division-University of Tennessee. (2)

CAPSIZING IN SUMMER VERSUS SPRING

In whitewater canoeing, one can count on probably being dumped at some point during the trip. Capsizing can be a shock to the system at any time of the year. It is paramount to be prepared mentally, physically and with gear—PFD—for unexpectedly being in the water. Expect the unexpected.

From a sociology stand point, according to American Whitewater.ORG (3):

“Risk is essential. There is no growth or inspiration in staying within what is safe and comfortable.”—Alex Noble

“…an emphasis on self-sufficiency, individualism and personal achievement – preferably under adverse circumstances – admiration of risk taking, admiration for skilled performance, especially in competitive situations, and high regard for freedom from both authority and tradition.”—Sociologist David Klein

Outdoor and wilderness recreation has expanded dramatically in the U.S. during the past two decades. Today 77% of Americans view outdoor recreation as an important part of their lives. All outdoor activities, and indeed most elements of daily life, contain some potential for injury. Some outdoor enthusiasts will seek the additional physical and mental challenges found in risk sports. These are skill-based, high-energy activities that contain unavoidably dangerous elements and require special training for prior to participating. Whitewater paddling and activities like skiing, rock climbing and mountain biking are considered risk sports.

Whitewater enthusiasts are often stereotyped as mindless thrill-seekers with a death wish. The reality is quite different. Paddlers represent a true cross-section of American society and include many highly educated professionals. They know the limits of their skills, and by choosing what rapids they run, they control the intensity of their experience. It is a life-long sport that nurtures a love for wild places and an appetite for low-impact, human powered travel. Extreme paddlers are especially calculating when exposing themselves to danger. Today 28% of all Americans currently participate in – or intend to participate in – this type of activity.

Whitewater paddlers, like other risk sport enthusiasts, approach their activity with a focus and intensity not often found in traditional outdoor recreation. They’re aware of the dangers and take concrete steps to avoid them. They purchase highly specialized equipment and work hard to develop the skills they need. They condition themselves mentally and physically and learn first aid and rescue skills before setting out. They have a strong sense of personal responsibility and a full understanding of the consequences of their actions. Drug and alcohol abuse is quite rare. Because of their expertise and involvement the actual risks they face are not much more than those encountered by inexperienced people in traditional outdoor recreation.

The risks of any active outdoor sport can be managed, but never eliminated. Dealing intelligently with danger is at the heart of the experience, and outdoor education programs are popular precisely because of this challenge. It’s not just about thrills. Learning paddling skills and executing them under pressure helps people develop coolness and courage. This in turn helps a person become more confident and self-reliant. In addition, teaching anyone, especially young people, to deal intelligently with danger helps develop good judgment. This has broad positive implications beyond the river.

According to the 2014 U.S. Naval Report (4) on United States recreational boating statistics, there were 105 rowing/paddling deaths of vessel operation at the time of death (not necessarily whitewater). There were 26 whitewater related deaths of vessel activity. In 2014 there were 75 canoe deaths (not necessarily whitewater), of which 4 involved rented vessels and 56 were not rented. Deaths ranged in ages from 11 to 80. Drowning accounted for 69 of the 75 canoe deaths. From the Naval Report it is not stated how many of the 26 related whitewater deaths were from canoes verses kayaks, nor does it breakdown the cause of death for whitewater.

Looking at statistics, just how many canoe paddlers were there in 2015? The Special Report of the 2015 PADDLESPORTS (5) states that canoeing had 10 million participants. Kayaking (any type) had 13 million participants. Rafting had 3.8 million participants and stand up paddle board had 2.8 million participants in 2015. The statistics did not break down the percentage of whitewater canoeing within the total canoe participants for 2015.

Statistically in 2014 (and 2015) there were millions and millions of U.S. paddlers and there were 26 whitewater related deaths of vessel activity (in 2014). Perhaps within this high risk sport of whitewater canoeing, the adventurer’s risk is more of a calculated risk, at least to some degree. Self-education, preparedness of mind, body and gear, and practicing safety (for example wearing a PFD, no substance abuse) contributes to a lower-risk factor.

CAPSIZING: THE TELLING What is it like to capsize? Capsizing happens suddenly, though perception can feel like slow motion because the adrenaline surges in the brain and body. Once the boat capsizes in the rapids, the body immediately submerges and there is a knee-jerk response of wanting to take a breath. In spring, the frigid water—at least the two times I’ve ever capsized and jumped into a spring river—is a shock like electricity to the mind. Such a shock, that it robbed me from taking a breath, and instead I force-gulped water.

During that first submersion, I had three clear thoughts:

- I’m in the water

- TOES-NOSE

- I think I am going to die

The realization that one is in the water, at least for me, was experienced like a question-statement. A little disbelief, a little actualization that I needed to get down to business of saving my life.

Toes-nose is the position anyone having fallen into the rapids needs to take…feet first with toes sticking out of the water. The body follows the feet. This protects your core body from bouncing off rocks and debris, such that your feet will hit river objects first, saving your head and torso.

Facing death, and in hindsight now, I take comfort in knowing that my initial thoughts were a conversation with God. I think I’m going to die was a calm, questioning thought in which I was speaking to the Creator. I was not panicked, nor was I resolved to the idea. Reassuringly, God answered immediately (still within that first submersion)…it is not your time. Once I heard this confirmation of “not my time”, I emerged from the water because of the buoyancy of my life jacket, or PFD, and began going down the rapids toes-nose.

Holding onto my paddle I could see my body was about to enter the first of what would be several of the typical whitewater’s “V” in the middle of the flow. Hold your breath, a calming reassuring thought entered my mind. I held my breath and popped up after the V. Breathe. I breathed without gasping, understanding the nature of the beast. In the V of a whitewater, the body will usually automatically move with the current into that direction. I was physically at the will of the rapids, but I knew I would be okay, and interestingly, I could no longer hear the water when I was in it, for I had become one with the rapids and bowed to the mercy of its will, not mine.

TWO MINUTES IN THE WATER Somewhere in the midst of the approximate two minutes, I made the decision to let go of my paddle because I realized I was trying to use it as a lever to hoist myself up higher in the water and instead I was submerging myself. So I let go. I saw a dromedary (a rubber bag that holds clean drinking water) and Ziploc snack bag. I grabbed those two items and hoped we would be able to retrieve the paddle later. My feet headed towards a huge boulder in a calmer eddy, but the water swirled me around the rock and I continued on. Coming around the boulder I changed positions to see if I could feel the bottom. I couldn’t. TOES-NOSE. Then the rapids were over and the flow of Big South Fork graduated to less than a swift current. I held my two items in one hand and side stroked to the beach shoreline where I could see the rest of my capsized party gathering.

Everyone was okay. We all worked together and retrieved all of our backcountry whitewater canoe gear. There is personal and group fortitude in this experience. There is strength and importance in its telling.

Author’s Note:

How one interprets a scary, life-threatening or catastrophic event at the initial onset when it first happens, is very important. Why? Because big personal events have a way of weaving themselves into the fabric of who we are. So it is important to spin the facts in a positive, character-building way, or “telling”. This doesn’t mean that the scary event wasn’t scary. It means you are making sure you interpret it in a positive strength-filled “telling”, so that your memories and story-telling of the scary event becomes a powerful life-positive event like a hero story and not a traumatic tragedy of doom.

Why? Because ten years from now you will be telling your own story of a personal event… and you will be better by building yourself in the “telling” of your story with strengths of character-building versus living in the shadows of fearful memories that might turn into post traumatic stress. — Mina Thevenin, LCSW

-

- WHITEWATER CANOEING RESOURCES

-

- 1. “KENTUCKY DEPARTMENT of FISH & WILDLIFE RESOURCES.”

Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Big South Fork . N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2016. <http://fw.ky.gov/Education/Pages/Big-South-Fork.aspx>.

2. United States. National Park Service. “Black Bear on the Plateau.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 2016. <https://www.nps.gov/biso/learn/nature/blackbear.htm>.

3. “Risk, Safety, and Personal Responsibility.” American Whitewater –. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2016. <http://www.americanwhitewater.org/content/Wiki/stewardship:risk>.

4. United States Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Coast Guard, Office of Auxillary and Boating Safety. 2014 Recreational Boating Statistics. (May 2015) pdf. “United States Coast Guard | Boating Safety.” United States Coast Guard | Boating Safety. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Apr. 2016. <https://www.uscgboating.org/>.

5. “Paddlesport Statistics – ACA | Canoe – Kayak – SUP – Raft – Rescue.”Paddlesport Statistics – ACA | Canoe – Kayak – SUP – Raft – Rescue. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Apr. 2016. <http://www.americancanoe.org/?page=Statistics>.

* All images were taken with a Samsung Galaxy S4 cell phone camera.

0 comments